|

Pitcher plants of the genus Sarracenia

catch insects in hollow fluid-filled

leaves, and have large red, yellow, or

pink flowers. |

I live in Florida, and was delighted to find out a number of years ago that we host here the greatest concentration of carnivorous plants in the United States. As the name implies, carnivorous plants capture digest, and consume animals, mostly small animals like insects. Everyone knows the famous venus fly trap (

Dionaea muscipula), which snaps shut quickly around an insect that touches its sensitive trigger hairs. That is one species that unfortunately does not grow naturally in Florida, though I've heard rumors of carnivorous plant enthusiasts secretly planting it in some of our bogs that may be similar to its native habitat in North and South Carolina.

What we do have here are six species of pitcher plants (

Sarracenia), five species of sundew (

Drosera), six species of butterwort (

Pinguicula), and 14 species of bladderwort (

Utricularia). Each is different in how it catches its prey.

|

Sarracenia flava is known to produce an alkaloid

drug that renders insect prey unable to crawl out of

the trap. |

|

The opening of the pitcher invites insects with mottled

coloration and prevents their escape with small, slippery

hairs. |

The pitcher plants have inflated, hollow leaves that fill with water. Insects fall or slide into these pitchers, often attracted by bright colors, nectar or scent. The walls of the pitchers are slippery due to wax or downward pointing hairs, so that insects that fall in cannot crawl back out. At least one species,

S. flava, has been found to secrete an alkaloid drug that inhibits the insects' ability to find their way out. Some pitchers produce digestive enzymes, others rely on bacteria and fungi to breakdown the animal tissues. The nutrients released can then be absorbed by the cells lining the chamber. Some of our

Sarracenias, such as

S. purpurea and

S. leucophylla, are wide open to rain water, which keeps them full at least during the rainy season. Others have lids, that keep out some of the rain, or curved tops that keep out most of the rain (

S. minor, S. psittacina). These latter may be keeping a tighter control on the concentration of digestive fluids, and secrete fluids into their chambers from their own tissues.

.JPG) |

Sarracenia purpurea collects rainwater to fill its traps. This is the most widespread species,

extending from the Florida panhandle all the way up into Canada. |

.JPG) |

The traps of Sarracenia psitticina lay along the ground and when flooded

can catch small fish and other aquatic animals. |

|

Sarracenia leucophylla occurs in the Florida panhandle and neighboring states,

like most of the other species. |

|

| Sarracenia minor has a curved top that limits the amount of rainwater that can get into the trap. This is the only species occurring south of the Florida panhandle region, and is found as far south as Hillsborough and Highlands Counties. |

.JPG) |

The long, grayish strands in this boggy roadside

are leaves of Drosera tracyi. |

|

Drosera capillaris is common on wet

sandy slopes throughout Florida. |

The leaves of sundews are covered with conspicuous glandular hairs. Insects get caught in the sticky secretions and then are digested by enzymes in the secretions. Two species (

Drosera tracyi and

D. filiformis) with long, slender leaves are found in the far north of the state. The others have roundish leaves.

Drosera capillaris is abundant throughout the state, quickly colonizing marshy areas around bodies of water (see

To self or not to self, the story of Drosera capillaris on the Botany Professor main page).

D. brevifolia is less common, but appears to be tolerant of slightly drier soil.

D. intermedia, with longer leaves, lives in standing water.

|

Drosera brevifolia is similar to D.

capillaris, but flowers tend to be

larger and there are sticky glands

on the flower stalk. |

|

The leaves of Drosera tracyi and D. filiformis

unroll like the fiddleheads of a fern frond. |

|

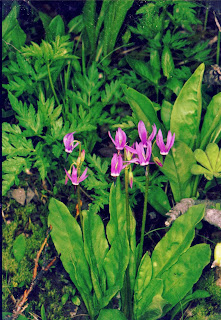

Pinguicula pumila is common in central

Florida and comes with white, bluish, or

purplish flowers. |

|

The traps of Pinguicula are simple, sticky

leaves. |

In the butterworts (

Pinguicula), the leaves are covered with short glands which give them a sticky, fly-paper like coating. The flowers are variously yellow, white, blue or violet, usually with a conspicuous nectar spur, and they live in wet to boggy soil.

|

| Pinguicula caerulea has sky blue flowers. |

|

The flowers of Utricularia inflata emerge from

star-like floating rosettes. Large, highly-

dissected trap-bearing leaves are beneath. |

|

A large population of Utricularia inflata

in a central Florida cypress swamp. |

|

Utricularia subulata grows on wet sand,

often near Drosera capillaris. |

|

Utricularia gibba is invisible until it sends

up its tiny yellow flowers. |

The bladderworts (

Utricularia) are the most numerous of Florida carnivores, with 14 species. They get their name from the tiny bladder-like traps on their underwater or subterranean leaves. These traps create a partial vacuum by actively pumping water out. when tiny crustaceans brush against sensitive trigger hairs, they are sucked into the traps where they are digested.

Utricularia floridana, U. foliosa, U. inflata, and

U. radiata are relatively large underwater plants, with just their flowers sticking up into the air.

U. olivacaea forms fine floating mats with tiny white flowers. The others form their masses of traps in wet soil. Bladderworts are cousins of the snapdragons and have similar yellow or purple flowers.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

+Acer+Negundo.JPG)

+Astragalus+missouriensis.JPG)

+Descurainia+richardsonii.JPG)

.JPG)

+Astragalus+mollissimus)).JPG)

+Oenothera+albicaulis.JPG)

+Melampodium+leucanthum.jpg)

+Equisetum.JPG)

+Dimorphocarpa+wislizeni.JPG)

+Nama+hispidum.JPG)